These “Lessons from Alaska” blog posts are written by Putney leader Braelei Hardt, who recounts several pivotal moments during their time leading our Middle School Alaska program and our Columbia Climate School program in Alaska. Please enjoy their accounts of these transformational experiences. Click these links to see the previous posts:

Games and Traditions

Several weeks before our Alaska program began, my co-leader and I grappled with an important decision. We’d just been told about The World Eskimo Indian Olympics (WEIO), a vibrant display of Northern indigenous culture that offers a rare glimpse into a world few outsiders ever witness. And for the first time, the games would coincide with our Putney Alaska program.

But our schedule for the trip was packed already, and we’d have to make room to attend this rare event. The trade-off was a day less in the embrace of Denali National Park’s wild majesty—a sacrifice, yes, but one we felt compelled to make. “This,” I said, “is a chance to see history, culture, and tradition alive and breathing.”

Once we were on the ground with our group, the drive to Fairbanks was a winding thread through the unfathomable expanse of Alaska’s stretching wilderness, each turn revealing vistas that seemed to have been painted by an artist’s wild brushstrokes. Our van was alive with the buzz of anticipation, punctuated by laughter and the occasional chorus of a road trip song. The students, their faces pressed against the windows, made a game of who could spot the most wildlife. At the time, we’d seen two dozen moose already.

Arriving at WEIO felt like stepping into another world. The air was electric with the energy of the games, a pulsating heart of tradition beating strong against the modern backdrop of Fairbanks, its bustling city center only blocks away. We were greeted by the event’s coordinator, her smile as wide as the Yukon. “We are honored to have you here,” she said, her voice a warm welcome, after we’d explained the intent of our visit. “To observe is to learn, and to learn is to respect. Here, you are not just visitors, but a part of a traditional celebration of cultures spanning generations, and geographies.” She continued, explaining to the students the difference between cultural appropriation and celebration. “It isn’t appropriation if you’re invited!” she beamed, explaining that most Native Alaskan groups are more than happy to share their ways with outsiders, and that adoption of those traditions is often seen as a compliment. Officially, she clarified, we were invited to enjoy these games.

As we mingled among the participants, the air was rich with the scent of smoked salmon and the sounds of rhythmic drumming. The event coordinator guided us through the throngs, her words weaving stories into the competitions before us. “Each game you’ll witness,” she explained, “is a test of survival, a display of the resilience and skill of our people, as understood by our ancestors.”

There was the Ear Pull, a game of pain endurance mirroring the trials of frostbitten hunts, each participant pulling on a string looped over their opponent’s ear until blood is drawn. The Four Man Carry, a game that is not about four men carrying something heavy—as I had assumed—but about one man carrying four others, echoed the strength required to bring hefty sustenance home from the unforgiving sea. In The Fish Fillet, a dance of knife, speed, and skill, competitors raced to clean their salmon the fastest. This last event culminated in a world record that left us all in awe—a teenage girl presented a fully fileted salmon as large as her torso in just 17 seconds.

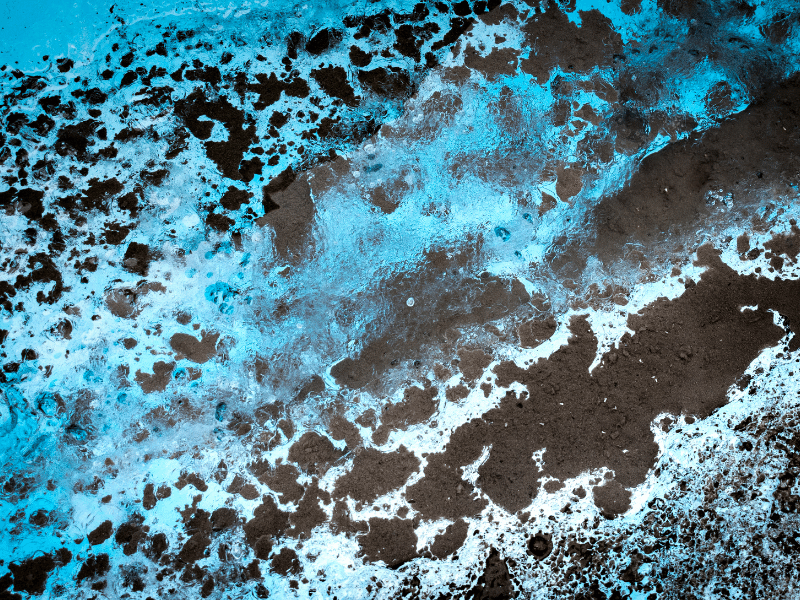

The Blanket Toss event, however, was where the magic truly unfolded. This game is based on traditional hunting and scouting practices, once a means for hunters to sight game over the expansive tundra. In it, a large blanket made of reindeer hide is spread out, its edges held by dozens of hands, ready to unite in a singular purpose. The coordinator explained to us, her voice infused with pride, “This is about balance, trust, and working together. Every pull is evidence of our connection with each other, and to the land.”

The Blanket Toss requires more hands than you might expect, and despite the robust turnout of this year’s games, the coordinator informed us that there simply weren’t enough Olympians available to pull the blanket.

“Do your travelers want to help?” she asked me, a mischievous sparkle in her eye. Of course they did.

Our students, a mix of excitement and nervous energy, joined the circle, their hands gripping the sturdy hide. The athlete, dressed in traditional garb, stepped onto the center of the blanket with a confidence born from years of practice.

An athlete in the World Eskimo Indian Olympics (WEIO) prepares for her Blanket Toss, supported by event staff and viewers alike. Fairbanks, Alaska, 2022. Credit: Braelei Hardt

Then, with a coordinated heave, the blanket came to life. The athlete was launched into the air, soaring high above the heads of the crowd. Each descent was met with an orchestrated pull, sending her skyward again, performing twists and turns in mid-air. The students, now integral to the rhythm of the toss, pulled with a synchronized effort, their faces alight with awe and exhilaration.

Watching them in that moment, my own hands yanking repeatedly on the hide blanket, I saw the barriers of time and culture blur. Here, in this age-old game, our Putney students had found a place among an ancient rhythm, a dance of community and celebration that had endured through generations. The athlete soared above, a shared experience of upliftment, binding us all in a moment of pure, unbridled joy.

As the event drew to a close, and the athlete landed his final, graceful descent, the students released the blanket, their faces flush with the thrill of the experience. “Did you see how high she went?” one of them exclaimed, his words tumbling out in a burst of excitement. “We did that, together!”

A year following this exhilarating experience at WEIO, I found myself once again leading a group through Alaska’s expanse. This time, it was with a group of high schoolers, eager and attentive, each carrying their own expectations and curiosities about the land and its people. Our journey led us to the Alaska Native Heritage Center, a place where the stories, traditions, and living history of Alaska’s native cultures converge.

The Heritage Center, nestled amidst the lush greenery of Anchorage, was a world away from the competitive energy of WEIO, yet it echoed the same deep reverence for culture and tradition. We were greeted by a young volunteer guide of Yupik descent, her nerves palpable as she faced her first group of visitors. My students, understandably sympathetic to the woes of public speaking, offered her smiles of encouragement, their empathy a bridge bypassing her anxiety.

As we traversed the grounds, each exhibit and demonstration offered a portal into the diverse lifestyles of Alaska’s indigenous peoples. The Tlingit lodge on site, a replica of their traditional homes, with a unique entrance protocol, was a lesson in trust and respect. “Turning your back as you enter is a sign of peace, a tradition that speaks volumes about the values held within these walls,” our guide explained, her confidence growing with each word. “Turning your back means you harbor no intent to attack.” Slowly, each of us entered the lodge with our backs turned.

Further along, we delved into the survival strategies of the Yupik and Saint Luis Island communities, particularly their ingenious, albeit stark, methods of dealing with polar bears. The students gathered around, a mix of curiosity and apprehension in their eyes, as the guide demonstrated the use of baleen strips—keratin teeth with a sharp tip used in filter-feeding whales. She held up a long piece of baleen, explaining how, when curled into a tight circle and secured with sinew, it served a grim yet necessary purpose. Once the baleen was swallowed by a polar bear, typically through bait in a seal carcass, the sinew ties would dissolve in the stomach acid, causing the baleen to spring open in the bear’s stomach and leading to the animal’s death by internal injury. “This was a grim practice borne out of necessity,” the guide explained. “For the safety of our communities living in close proximity to these powerful predators.”

The reality of this practice sparked a complex discussion among the students. For many, the idea of deliberately harming a polar bear was jarring, contrasting sharply with their perceptions of wildlife conservation. “It’s so different from what we’re used to thinking about polar bears,” one student remarked, a hint of realization in her voice. “I think we see them as distant, almost mythical creatures to be saved, but I’ve never really thought about what it’s like to live alongside them.”

As the day waned, the students gathered in the auditorium for the Center’s nightly dance performance. The rhythmic drumming of a seal-skin drum and the resonant hymns in the Yupik language filled the air, a powerful expression of cultural pride and joy.

“Would you like to learn?” the drummer asked after the dance, speaking to our group. Every student leapt at the opportunity. After several practice runs, their initial awkward movements soon gave way to a harmonious performance, a shared celebration that transcended cultural boundaries.

Click here to watch our students practice the Yupik ‘Bird Dance’ at the Alaska Native Heritage Center, Anchorage, Alaska, 2023. Credit: Braelei Hardt

“What does the song mean?” I asked the performers afterward, curious about the hymn that had united us all.

“It’s a dance of happiness,” our instructor replied. “A celebration of family, friends, and the joy of being together.” And indeed, as the students repeatedly hummed and twirled to the tune in the days that followed, it became clear that the Bird Dance had woven its way into their hearts, an ever-present reminder of the unity and connection they had experienced on their first day together.

Click these links to learn more about our Career program in Alaska and our collaboration with the Columbia Climate School.